|

Are new scientific discoveries revealing connections with a spiritual view of life?

Fritjof Capra argues that they are. The view of science and religion as a dichotomy has a long history, especially in the Christian tradition. Yet there are many scientists who see no intrinsic dichotomy between science and religion, or science and spirituality. At the very core of this confusing situation, in my view, lies the failure to distinguish clearly between spirituality and religion. To resolve this confusion, we need to examine the meaning of both, as well as the relationship between religion and spirituality.

Spirit and spirituality For a proper understanding of spirituality, it is useful to review the original meaning of 'spirit'. The Latin spiritus means ‘breath’, which is also true for the related Latin word anima, the Greek psyche and the Sanskrit ātman. The common meaning of these terms indicates that the original meaning of spirit in many ancient philosophical and religious traditions, in the west as well as in the east, is ‘breath of life’. Since respiration is indeed a central aspect of the metabolism of all but the simplest forms of life, the breath of life seems to be a perfect metaphor for the network of metabolic processes that is the defining characteristic of all living systems. It is what we have in common with all living beings. It nourishes us and keeps us alive. Spirituality is usually understood as a way of being that flows from a certain profound experience of reality, which is known as ‘mystical’, ‘religious’, or ‘spiritual’ experience. There are numerous descriptions of this in the literature of the world’s religions, which tend to agree that it is a direct, non-intellectual experience of reality with some fundamental characteristics that are independent of cultural and historical contexts. David Steindl-Rast, an Austrian American Benedictine monk who has spent much of his long life working with various religious traditions, as well as on the interaction between science and spirituality, characterises spiritual experience as moments of heightened aliveness. "Our spiritual moments", he writes, "are those moments when we feel most intensely alive." Buddhists refer to this heightened mental alertness as ‘mindfulness’, and they emphasise that mindfulness is deeply rooted in the body. Spiritual experience is an experience of aliveness of mind and body as a unity. Moreover, this experience of unity transcends not only the separation of mind and body, but also the separation of self and world. The central awareness in these spiritual moments is a profound sense of oneness with all, a sense of belonging to the universe as a whole. This sense of oneness with the natural world is fully borne out by the new systemic conception of life that has recently emerged at the forefront of science. As we understand how the roots of life reach deep into basic physics and chemistry, how the unfolding of complexity began long before the formation of the first living cells, and how life has evolved for billions of years by using again and again the same basic patterns and processes, we realise how tightly we are connected with the entire fabric of life. Spirituality and religion Spirituality, then, is a way of being grounded in a certain experience of reality that is independent of cultural and historical context. Religion is the organised attempt to understand spiritual experience, to interpret it with words and concepts, and to use this interpretation as the source of moral guidelines for the religious community. There are three basic aspects to religion: theology, morals and ritual. In theistic religions, theology is the intellectual interpretation of the spiritual experience, of the sense of belonging, with God as the ultimate reference point. Morals, or ethics, are the rules of conduct derived from that sense of belonging; and ritual is the celebration of belonging by the religious community. All three of these aspects depend on the religious community’s historical and cultural context. Theology was originally understood as the intellectual interpretation of the theologians’ own mystical experience. Indeed, during the first thousand years of Christianity virtually all of the leading theologians – the so-called Church Fathers – were also mystics. Over the subsequent centuries, however, during the scholastic period, theology became progressively fragmented and divorced from the spiritual experience that was originally at its core. With the new emphasis on purely intellectual theological knowledge came a hardening of the language. Whereas the Church Fathers repeatedly asserted that religious experience could not be adequately expressed in words, and therefore expressed their interpretations in terms of symbols and metaphors, the scholastic theologians formulated the Christian teachings in dogmatic language and required that the faithful accept these formulations as the literal truth. In other words, Christian theology became more and more rigid and fundamentalist, devoid of authentic spirituality. This rigid position of the Church led to the well-known conflicts between science and fundamentalist Christianity that have continued to the present day. The central error of fundamentalist theologians was, and is, to adopt a literal interpretation of religious symbols and metaphors. Once this is done, any dialogue between religion and science becomes frustrating and unproductive. Spiritual experience is also known as a mystical experience, because it is an encounter with mystery. Spiritual teachers throughout the ages have insisted that the experience of a profound sense of connectedness, of belonging to the cosmos as a whole, which is the central characteristic of mystical experience, is ineffable – that is, incapable of being adequately expressed in words or concepts – and they often describe it as being accompanied by a deep sense of awe and wonder, together with a feeling of great humility. Scientists, in their systematic observations of natural phenomena, do not consider their experience of reality as ineffable. On the contrary, they attempt to express it in technical language, including mathematics, as precisely as possible. However, the fundamental interconnectedness of all phenomena is a dominant theme also in modern science, and many of our great scientists have expressed their sense of awe and wonder when faced with the mystery that lies beyond the limits of their theories. Albert Einstein, for one, repeatedly expressed such feelings, as in the following celebrated passage: “The fairest thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion which stands at the cradle of true art and true science… Enough for me the mystery of the eternity of life, and the inkling of the marvellous structure of reality, together with the single-hearted endeavour to comprehend a portion, be it ever so tiny, of the reason that manifests itself in nature.” Now let us turn to the two other aspects of religion: morals and ritual. Morals, or ethics, are the rules of conduct derived from the sense of belonging that lies at the core of the spiritual experience, and ritual is the celebration of that belonging. Both ethics and ritual develop within the context of a religious community. Ethical behaviour is always related to the particular community to which we belong. When we belong to a community, we behave accordingly. In today’s world, there are two relevant communities to which we all belong. We are all members of humanity, and we all belong to the global biosphere. We are members of oikos, the Earth Household, which is the Greek root of the word ‘ecology’, and as such we should behave as the other members of the household behave – the plants, animals and micro-organisms that form the vast network of relationships that we call the web of life. The outstanding characteristic of the Earth Household is its inherent ability to sustain life. It behoves us, as members of the global community of living beings, to behave in such a way that we do not interfere with this inherent ability. This is the essential meaning of ecological sustainability. As members of the human community, we should behave in a way that reflects respect for human dignity and basic human rights. The original purpose of a religious community was to provide opportunities for its members to relive the mystical experiences of the religion’s founders. For this purpose, religious leaders designed special rituals within their historical and cultural contexts. These rituals may involve special places, robes, music, incense and various ritualistic objects – even psychedelic drugs. In many religions, these special means to facilitate mystical experience become closely associated with the religion itself and are considered sacred. Modern physics and eastern mysticism Scientists and spiritual teachers pursue very different goals. While the purpose of scientists is to find explanations for natural phenomena, that of spiritual teachers is to change a person’s self and way of life. However, in their different pursuits, both are led to make statements about the nature of reality that can be compared. Among the first modern scientists to make such comparisons were some of the leading physicists of the 20th century, who had struggled to understand the strange and unexpected reality revealed to them in their explorations of atomic and subatomic phenomena. In the 1950s, several of these scientists – Werner Heisenberg, Niels Bohr and others – published popular books about the history and philosophy of quantum physics, in which they hinted at remarkable parallels between the worldview implied by modern physics, and the views of eastern spiritual and philosophical traditions. During the 1960s, there was a strong interest in eastern spiritual traditions in Europe and North America, and many scholarly books on Hinduism, Buddhism and Taoism were published by eastern and western authors. At that time, the parallels between these eastern traditions and modern physics were discussed more frequently, and a few years later I explored them systematically in my book The Tao of Physics. After its publication in 1975, numerous books appeared in which physicists and other scientists presented similar explorations of the parallels between physics and mysticism. Other authors extended their enquiries beyond physics, finding similarities between eastern thought and certain ideas about free will, death and birth, and the nature of life, mind and consciousness. Similar parallels have been drawn with western mystical traditions. Deep ecology and spirituality The extensive explorations of the relationships between science and spirituality over the past three decades have made it evident that the sense of oneness that is the key characteristic of spiritual experience is fully confirmed by the understanding of reality in contemporary science. Hence there are numerous similarities between the worldviews of mystics and spiritual teachers – both eastern and western – and the systemic conception of Nature that is now being developed in several scientific disciplines. The awareness of being connected with all of Nature is particularly strong in ecology. Connectedness, relationship and interdependence are fundamental concepts of ecology; and connectedness, relationship and belonging are also the essence of religious experience. I believe therefore that ecology – and in particular the philosophical school of deep ecology – is the ideal bridge between science and spirituality. When we look at the world around us, we find that we are not thrown into chaos and randomness, but are part of a great order, a grand symphony of life. Every molecule in our bodies was once a part of previous bodies – living or non-living – and will be a part of future bodies. In this sense, our bodies will not die but will live on, again and again, because life lives on. Moreover, we share with the rest of the living world not only life’s molecules, but also its basic principles of organisation. Indeed, we belong to the universe, and this experience of belonging can make our lives profoundly meaningful. This article was first published in Resurgence & Ecologist issue 310 Sep/Oct 2018. All rights are reserved to The Resurgence Trust: www.resurgence.org Ascension Now was granted permission to publish this article. |

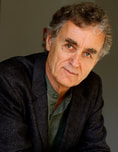

About the Author:

Fritjof Capra, physicist and systems theorist, is a Fellow of Schumacher College and serves on the Council of 'Earth Charter International'.

His books include The Tao of Physics, The Web of Life and The Hidden Connections. He is co-author, with Pier Luigi Luisi, of the multidisciplinary textbook The Systems View of Life, on which his new online course at www.capracourse.net is based.

His books include The Tao of Physics, The Web of Life and The Hidden Connections. He is co-author, with Pier Luigi Luisi, of the multidisciplinary textbook The Systems View of Life, on which his new online course at www.capracourse.net is based.