What and Where Is Consciousness?

Aristotle taught that the brain exists merely to cool the blood and is not involved in the process of thinking.

This is true only of certain persons.

~ Will Cuppy

This is true only of certain persons.

~ Will Cuppy

|

Is the Brain Really Necessary?

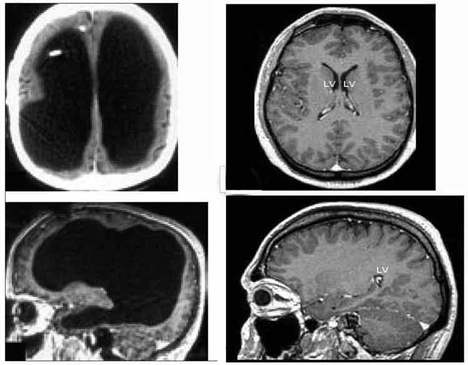

This was the question asked by British neurologist John Lorber when he addressed a conference of pædiatricians in 1980. Such a frivolous sounding question was sparked by case studies Lorber had been involved in since the mid-60s. The case studies involved victims of an ailment known as hydrocephalus, more commonly known as "water on the brain". The condition results from an abnormal build up of cerebrospinal fluid and can cause severe retardation and death if not treated. Two young children with hydrocephalus referred to Lorber presented with normal mental development for their age. In both children, there was no evidence of a cerebral cortex. One of the children died at age 3 months, the second at 12 months. He was still following a normal development profile with the exception of the apparent lack of cerebral tissue shown by repeated medical testing. An account of the children was published in Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. Later, a colleague at Sheffield University became aware of a young man with a larger than normal head. He was referred to Lorber even though it had not caused him any difficulty. Although the boy had an IQ of 126 and had a first class honours degree in mathematics, he had "virtually no brain". A non-invasive measurement of radio density known as a CAT scan showed the boy's skull was lined with a thin layer of brain cells to a millimeter in thickness. The rest of his skull was filled with cerebrospinal fluid. The young man continues a normal life with the exception of his knowledge that he has no brain. Although anecdotal accounts may be found in medical literature, Lorber is the first to provide a systematic study of such cases. He has documented over 600 scans of people with hydrocephalus and has broken them into four groups:

Of the last group, which comprised less than 10% of the study, half were profoundly retarded. The remaining half had IQs greater than 100. Skeptics have claimed that it was an error of interpretation of the scans themselves. Lorber himself admits that reading a CAT scan can be tricky. He also has said that he would not make such a claim without evidence. In answer to attacks that he has not precisely quantified the amount of brain tissue missing, he added, "I can't say whether the mathematics student has a brain weighing 50 grams or 150 grams, but it is clear that it is nowhere near the normal 1.5 kilograms." Many neurologists feel that this is a tribute to the brain's redundancy and its ability to reassign functions. Others, however, are not so sure. Patrick Wall, professor of anatomy at University College, London states "To talk of redundancy is a cop-out to get around something you don't understand." Norman Geschwind, a neurologist at Boston's Beth Israel Hospital agrees: "Certainly the brain has a remarkable capacity for reassigning functions following trauma, but you can usually pick up some kind of deficit with the right tests, even after apparently full recovery." References: Anthony Smith The Mind New York Viking Press, 1984, page 230 Roger Lewin "Is Your Brain Really Necessary?"Science 210 December 1980, page 1232 Source: web.syr.edu 30 October 1993 Single Brain Cell's Power Shown

Individual cells may be more powerful than thought

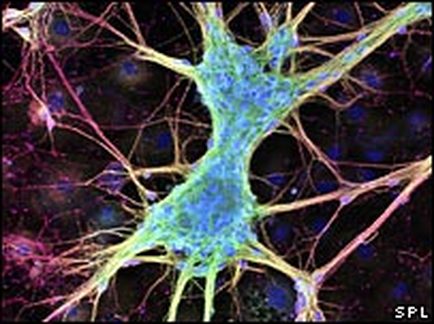

There could be enough computing ability in just one brain cell to allow humans and animals to feel, a study suggests. The brain has 100 billion neurons but scientists had thought they needed to join forces in larger networks to produce thoughts and sensations. The Dutch and German study, published in Nature, found that stimulating just one rat neuron could deliver the sensation of touch. One UK expert said this was the first time this had been measured in mammals.

The complexity of the human brain and how it stores countless thoughts, sensations and memories are still not fully understood. Researchers believe connections between individual neurons, forming networks of at least 1,000, are the key to some of its processing power. However, in some creatures with simpler nervous systems, such as flies, a single neuron can play a more significant role. The latest research suggests this may also be true in "higher" animals. The team, from the Humboldt University in Germany and the Erasmus Medical Centre in the Netherlands, stimulated single neurons in rats and found this was enough to trigger a behavioural response when their whiskers were touched. A second research project from the US suggests the computational ability of the brain cell could be even more complex, with different synapses - the many junctions between neurons and other nerve cells - able to act independently from those found elsewhere on the same cell. This could mean that, within a single neuron, different synapses could be storing or processing completely different bits of information. Dr Douglas Armstrong, the deputy director of the Edinburgh Centre for Bioinformatics, said the research did not mean all neurons had an individual role to play but that, in some instances, they might be capable of working alone with measurable results. He said: "The generally accepted model was that networks or arrays make decisions and that the influence of a single neuron is smaller - but this work and other recent studies support a more important role for the individual neuron. These studies drive down the level at which relevant computation is happening in the brain." Source: news.bbc.co.uk 22 December 2007 |

|