Specifically, they looked at pulses of noise in an ultraviolet photometer carried aboard many polar orbiting Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP) satellites. When high-energy protons in the SAA pass through these sensors, they produce spurious signals--or, in the case of this study, valuable data. By monitoring the rate of spurious UV pulses, the researchers were able to trace the outlines of the anomaly and monitor its evolution over a period of years.

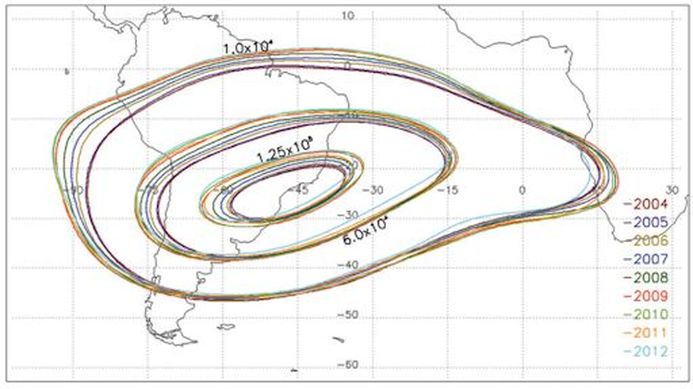

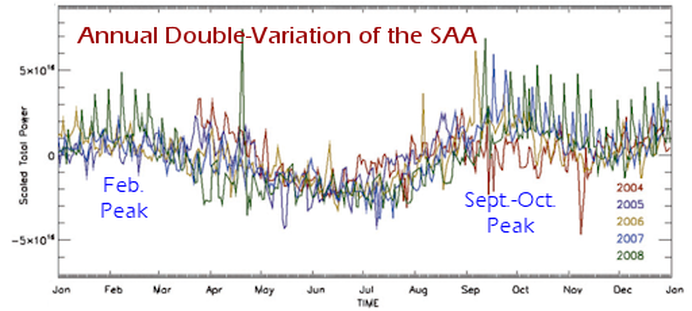

They found that the anomaly is slowly drifting north and west at rates of 0.16 deg/yr and 0.36 deg/yr, respectively. Currently, it is most intense over a broad region centered on Sao Paulo, Brazil, including much of Paraguay, Uruguay, and northern Argentina. They also detected a seasonal variation: On average, the SAA is most intense in February and again in September-October. In this plot, yearly average counts have been subtracted to reveal the double-peaked pattern:

The solar cycle matters, too, as the data revealed a yin-yang anti-correlation with sunspots. "During years of high solar activity, the radiation intensity is lower, while during solar quiet years the radiation intensity is higher," writes Schaefer.

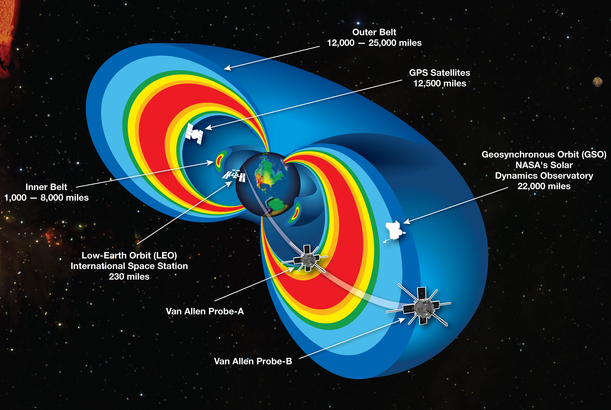

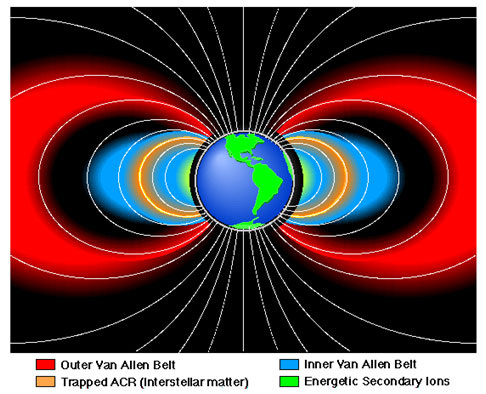

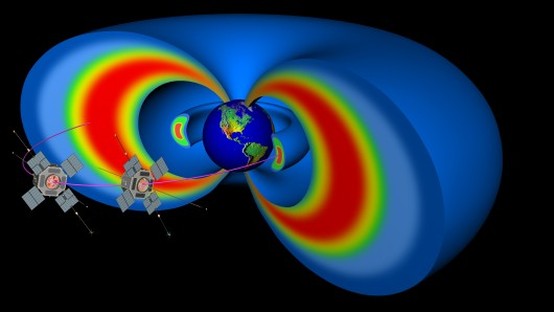

According to orthodox thinking, the SAA reaches down from space to within about 200 km of Earth's surface. Below that altitude, its effects should be mitigated by the shielding of Earth's atmosphere and geomagnetic field. To test this idea, Spaceweather.com and Earth to Sky Calculus have undertaken a program to map the SAA from below using weather balloons equipped with radiation sensors. Next week we will share the results of our first flight from a launch site in Chile. Stay tuned!

www.spaceweather.com

RSS Feed

RSS Feed