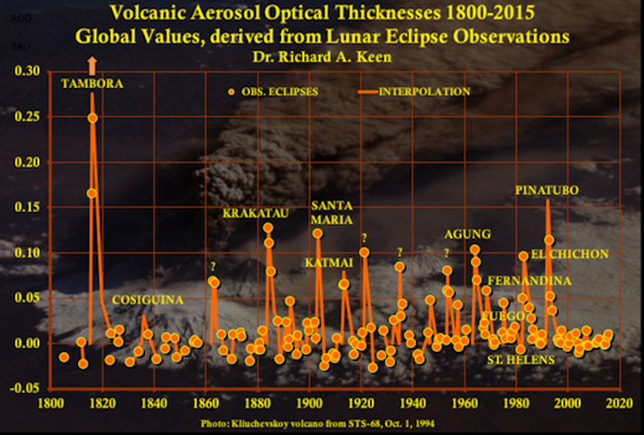

"During a lunar eclipse, most of the light illuminating the Moon passes through Earth's stratosphere where it is reddened by scattering," he says. "If the stratosphere is loaded with dust from volcanic eruptions, the eclipse will be dark. The cataclysmic explosion of Tambora in 1815, for instance, turned the Moon into a dark, starless hole in sky during two subsequent eclipses."

But Earth is experiencing a bit of a volcanic lull. We haven't had a major volcanic blast since 1991 when Mt Pinatubo awoke from a 500 year slumber and sprayed ten billion cubic meters of ash, rock and debris into Earth's atmosphere. Recent eruptions have been puny by comparison and have failed to make a dent on the stratosphere. To Keen, the interregnum means one thing: "This eclipse is going to be bright and beautiful."

by R. A. Keen

"Mt. Pinatubo finished a 110-year episode of frequent major eruptions that began with Krakatau in 1883," he says. "Since then, lunar eclipses have been relatively bright, and the Jan. 31st eclipse should be no exception."

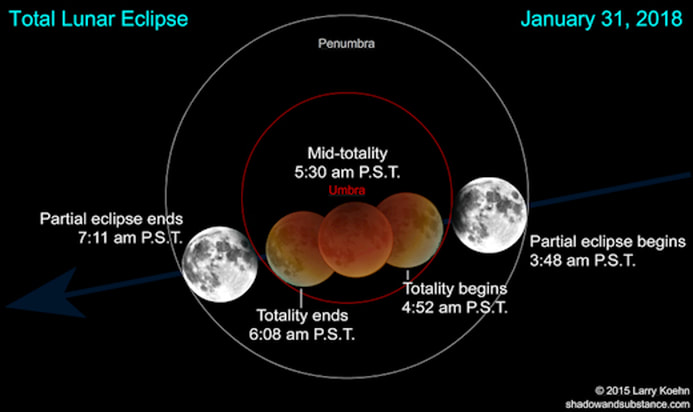

In the USA, the best time to look is during the hours before sunrise. Western states are favored: The Moon makes first contact with the core of Earth's shadow at 3:48 am Pacific Time, kicking off the partial eclipse. Totality begins at 4:52 am PST as Earth's shadow engulfs the lunar disk for more than an hour. "Maximum orange" is expected around 5:30 am PST. Easternmost parts of the USA will miss totality altogether.

www.spaceweather.com

RSS Feed

RSS Feed