"We have found Kelvin-Helmholtz waves rippling down the flanks of Earth's magnetosphere", says Shiva Kavosi of Embry–Riddle Aeronautical University, lead author of the Nature paper. "NASA spacecraft are surfing the waves, and directly measuring their properties".

This was first suspected in the 1950s by theoreticians who made mathematical models of solar wind hitting Earth's magnetic field. However, until recently it was just an idea; there was no proof the waves existed. When Kavosi's team looked at data collected by NASA's THEMIS and MMS spacecraft since 2007, they saw clear evidence of Kelvin Helmholtz instabilities.

"The waves are huge" says Kavosi. "They are 2 to 6 Earth radii in wavelength and as much as 4 Earth radii in amplitude."

Credit: Shiva Kasovi. [full-sized animation]

A key finding of Kavosi's paper is that the waves prefer equinoxes. They appear 3 times more frequently around the start of spring and fall than summer and winter. Researchers have long known that geomagnetic activity is highest around equinoxes. Kelvin-Helmholtz wave activity could be one reason why.

Our planet's seasonal dependence of geomagnetic activity has always been a bit of a puzzle. After all, the sun doesn't know when it's autumn on Earth. One idea holds that, around the time of the equinoxes, Earth's magnetic field links to the sun's because of the tilt of Earth's magnetic poles. This is called the Russell-McPherron effect after the researchers who first described it in 1973. Kavosi's research shows that Kelvin-Helmholtz waves might be important, too.

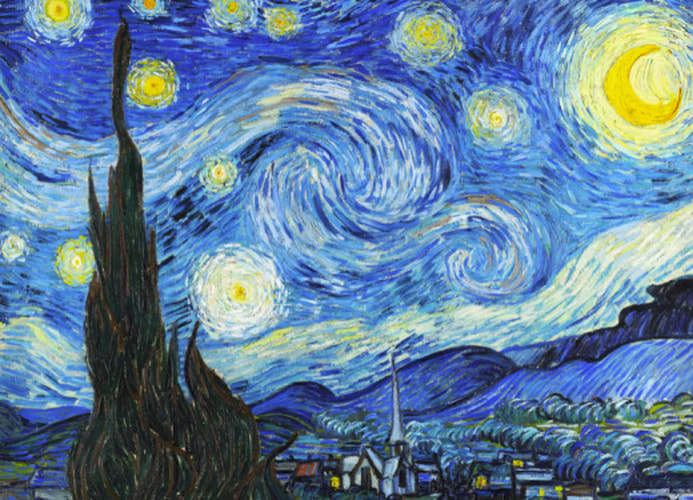

Northern autumn has just begun, which means Kelvin Helmholtz waves are rippling around our planet, stirring up "Starry Night" auroras. Happy autumn!

www.spaceweather.com

RSS Feed

RSS Feed